Brandon Thibodeaux

About

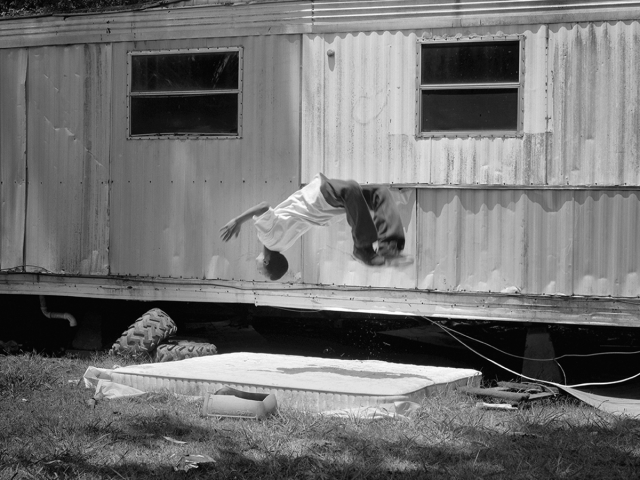

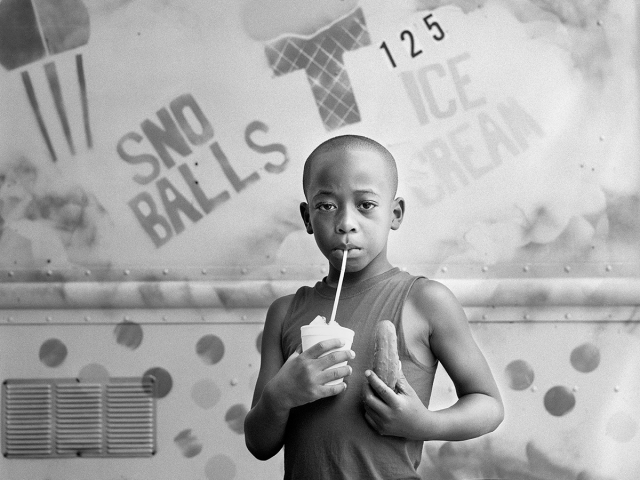

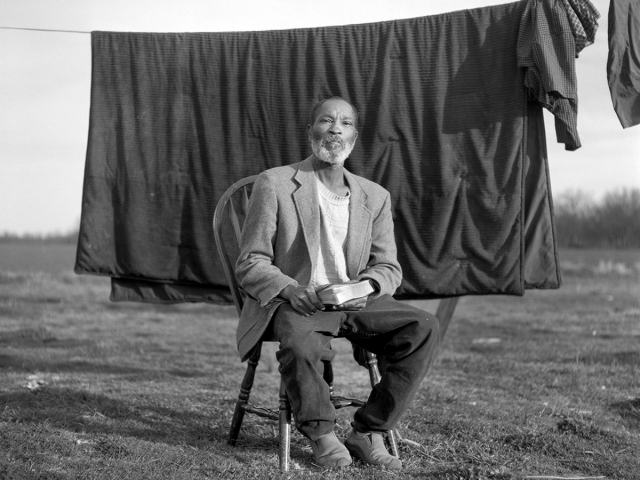

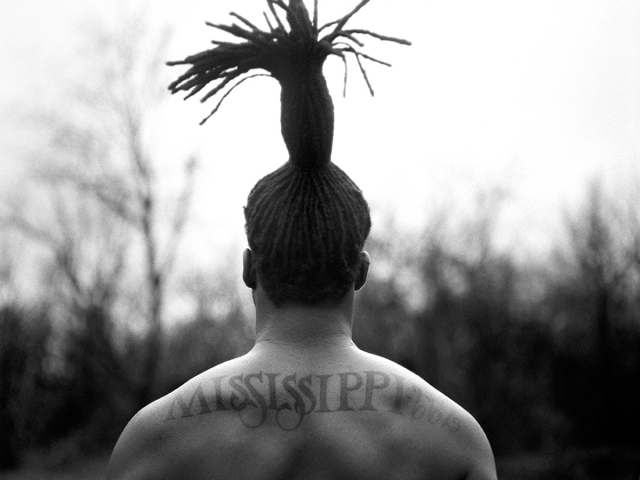

Brandon Thibodeaux (https://www.brandonthibodeaux.com/) is a member of the New York-based photography collective MJR. His career in photography began at a small daily newspaper in southeast Texas while studying photography at Lamar University in Beaumont, TX, under Keith Carter. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Photojournalism from the University of North Texas with a specialization in International Development. He currently resides in Dallas, TX, where he works for clients like Shell Oil International, Smithsonian Magazine, Mother Jones, Monocle, FT Weekend Magazine, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal, among others, and is also a guest instructor with the Santa Fe and Maine Media Workshops. His work in the Mississippi Delta entitled, When Morning Comes, has been recognized by American Photo Magazine, PDN, New York Times Lens Blog, Time.com, and is internationally exhibited in galleries and museums. The Brooklyn-based publishing company, Red Hook Editions, published his work from When Morning Comes in October 2017 under the title, In That Land of Perfect Day. Works from this series are included in the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, the Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans, and in the southern photography collection, The Do Good Fund, Inc. In 2009 he joined the ranks of the Getty Reportage Emerging Talent. In 2012 The Oxford American listed him as being one of their 100 Under 100 New Superstars of Southern Art, and in 2013 his work in the Mississippi Delta was award the Critical Mass Top 50 Solo Show Award. He is the 2014 Michael P. Smith Fund for Documentary Photography recipient and 2016 Palm Springs Portfolio Review Prize winner.

Gallery

LACP Interviews Brandon Thibodeaux

LACP asks Brandon Thibodeaux ten questions about his background, career in and beliefs about photography

Los Angeles Center of Photography: What kind of photographer are you?

Brandon Thibodeaux: By trade I work as a freelance corporate and editorial photographer while my personal work bridges a divide between fine art and documentary photography. For me, photography is about building relationships and telling stories. My personal work has always had a sprinkling of self discovery mixed within documentary pursuits. I think that’s why I’m so enticed by portraiture, and long form narratives that allow me the time to develop an intimacy with the people that I’m photographing. I tend to leave behind as much as I take away.

I’ve been working on one main project for the better part of 9 years now and finally published my first book of the work last summer. This personal project, In That Land of Perfect Day, was a departure from my daily work and became a vehicle for navigating the world of fine art photography in recent years.

LACP: How long have you been shooting?

BT: I have been shooting since 2000, but my professional career began roughly 16 years ago.

LACP: Where did you get your training?

BT: I studied at Lamar University in my hometown, Beaumont, TX, and later transferred to the University of North Texas near Dallas, TX, where I obtained degrees in Photojournalism and International Development. During college I worked full time for my local paper and when I transferred schools I interned and later began freelancing for the Dallas Morning News.

Photography introduced me to all walks of life and allowed me to interpret my experiences in a tangible way. With time, the relationship between my curiosities and this chosen medium grew stronger and I eventually I began freelancing full time. Every assignment could be seen as training, even today.

LACP: When did you know you wanted to devote your life to photography?

BT: I’d say from the beginning. I discovered photography after spending my teenage years battling cancer. I needed an elective my freshman year and it just so happened that my roommate said his uncle taught photography at our local university, come to find out his uncle is the fine art photographer, Keith Carter. So, on one hand I found myself immersed in the history and art of black and white photography in the darkroom with Keith, while on the other hand I was simultaneously developing a practical career-oriented application for the craft by working at the local newspaper. It didn’t take long for me to fall in love with it all. I was shooting everything under the sun early on. I used to say that that first newspaper job was a social engagement boot camp of sorts. I could be at a kindergarten class at 8:30am, a homicide at noon, and a high school basketball game at 7:30, ending with enough time to develop my film for the morning paper. This was really something for a 21-year-old, learning how to engage and carry myself among all walks of life. The only thing that’s changed today is I’m working for global clients.

LACP: Did you ever come close to giving up?

BT: Early in my freelance career things were tough, really tough. Most young freelancers would be lying to you if they said they weren’t keeping their small business afloat by using credit cards to finance projects and living expenses. By the time I graduated in the early 2000’s the old career path for photojournalists had nearly ceased to exist. Traditionally you’d have an internship or two, work for a small paper, or if you were good enough you’d start at a medium size paper and hopefully make it to a large daily and stay there until you retired.

Unfortunately, there was a large band of us coming out of college at that time that were unequipped to dive into small business ownership. Freelancing just wasn’t taught in the classroom. You put yourself out there and hoped if you worked hard enough, made the right connections, and surrounded yourself with creative people that eventually it would all pay off. Lots of us pooled together and began collectives to support our creative drive. The remnants of some of those early American collectives are still around today. The editorial photography circle is very small and close knit and the camaraderie from the collective and the photo community at large are what kept me afloat mentally back then.

LACP: Have you sacrificed anything by being a photographer?

BT: Oh gosh, you sacrifice a lot in this field. Steady income and creature comforts mostly. Everything financially has gone to funding my personal work and it’s the personal work that drives my appeal to clients. Owning a creative business is a never-ending battle against self-doubt, finance and stability. That all said, I could have never survived working a regular 9-5 building someone else’s dream. And over time the hard work led to consistency.

LACP: What have you gained by being a photographer?

BT: Absolutely everything. Photography is such a personal experience to me. It’s made me who I am. It’s not just a way of keeping a comfortable roof over my head, it is what shaped and molded all the inner workings of that head.

LACP: What classes do you teach at LACP?

BT: For the past few years I have been teaching classes about developing personal projects and harnessing their potential to find commissioned work.

LACP: What do you love most about teaching?

BT: The engagement. The two way flow of ideas.

LACP: What advice would you give someone who is thinking about making a career in photography?

BT: Go into it knowing that it’s a rocky road. Find who you are because your photography is a natural extension of that. If passion runs through your images, your images will stir that same passion in your viewers. Be open to criticism, put yourself out there, be prepared to take personal and financial risks but be even more prepared to know when you’ve hit a dead. Then, take what you’ve learned and begin again. There’s a difference between quitting and stopping. Stopping is when it’s time to reevaluate and change course. Quitting is when you look back 30 years later and regret never following your heart. Never quit.